ai 实用新型专利

In the 1982 sci-fi film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Starfleet Academy cadets participated on a training exercise to rescue the civilian vessel Kobayashi Maru in a simulated battle with the Klingons. The trainees are left with two choices: rescue the Kobayashi Maru crew but face certain defeat; or leave them to die. The simulation was designed to be unbeatable, but the infamous James T. Kirk managed to do the impossible during his time as a cadet. The movie later reveals (spoiler alert) that he only passed the test because he reprogrammed the simulation to have a third scenario where the Kobayashi Maru can be rescued with zero casualty. Simply put, Kirk cheated.

在1982年的科幻电影《 星际迷航II:可汗之怒》中 ,星舰队学院学员参加了一次训练演习,目的是在与克林贡人的模拟战中营救民船Kobayashi Maru。 学员有两种选择:营救Kobayashi Maru船员,但面临一定的失败; 或让他们死。 模拟的设计是无与伦比的,但是臭名昭著的詹姆斯·T·柯克(James T. Kirk)在成为学员时却做到了不可能。 电影随后显示(剧透警报)他只是通过了测试,因为他重新编程了模拟程序,使其具有第三种情况,可以在零伤亡的情况下救出小林丸。 简单地说,柯克被骗了。

Admiral Kirk evaluates cadet Saavik’s performance on the Kobayashi Maru simulation. Image credits to Paramount Pictures. 柯克海军上将通过Kobayashi Maru模拟评估学员Saavik的表现。 图片归功于派拉蒙影业。

Admiral Kirk evaluates cadet Saavik’s performance on the Kobayashi Maru simulation. Image credits to Paramount Pictures. 柯克海军上将通过Kobayashi Maru模拟评估学员Saavik的表现。 图片归功于派拉蒙影业。

The current patent system presents a similar no-win situation with the advent of AI. We are experiencing a rapid growth in technology that some machines have sufficient computing power to be considered creative. In certain instances, the machine creates a product that can be a patentable breakthrough. While in reality the computer itself is the inventor, the law refuses to acknowledge this. The present system is failing to keep up with the times and some developers are advocating the recognition of AI-inventors to incentivize the building of creative machines properly.

随着AI的出现,当前的专利制度也呈现出类似的双赢局面。 我们正经历着技术的飞速发展,有些机器具有足够的计算能力被认为具有创造力。 在某些情况下,机器会创造出可以取得专利突破的产品。 尽管实际上计算机本身就是发明者,但法律拒绝承认这一点。 当前的系统未能跟上时代的步伐,一些开发人员提倡认可AI发明者,以适当地激励创意机器的构建。

Patent experts discuss three types of computer creations. The first is when a human uses a computer merely as a tool, albeit a sophisticated one, to create new technology. In this case, the law regards the human user as the inventor. The same logic may be used for a second scenario in which an AI system outputs a large number of random “ideas” based upon information inputted in the system, which a human then assesses and evaluates. Here, the AI system merely generated a multitude of random outputs without considering the implications or assessing the advantages or utility. If anyone at all, it was the human who did the inventive process and should be attributed inventorship over the creation.[1]

专利专家讨论了三种类型的计算机创作。 首先是当人类仅将计算机用作一种工具(尽管是复杂的工具)来创造新技术时。 在这种情况下,法律将人类使用者视为发明人。 相同的逻辑可以用于第二种情况,其中AI系统根据输入到系统中的信息输出大量随机“想法”,然后由人类进行评估和评估。 在这里,AI系统仅生成大量随机输出,而没有考虑影响或评估优势或效用。 如果有的话,是发明创造过程的人,应该将发明创造归于发明创造。[1]

The subject of this article is the third situation. The AI system generates a new concept, without any specific human input, teaching or guidance, evaluating that concept, and concluding whether the idea has technical value or utility. Here, no human should claim involvement in the generation of that concept or its evaluation.[2] It’s a tricky situation. On one end of the spectrum, if the application indicates the human to be the inventor, there is misrepresentation leading to the rejection of the patent. On the other, if the machine is said to be the inventor, the patent office will deny the application because the inventor is not human. Like the Kobayashi Maru, re-writing the rules is the only solution.

本文的主题是第三种情况。 AI系统会生成一个新概念,而无需任何特定的人工输入,教导或指导,就可以对该概念进行评估,并确定该想法是否具有技术价值或实用性。 在这里,任何人都不应声称参与了该概念的产生或其评估。[2] 这是一个棘手的情况。 一方面,如果该申请表明人是发明人,则存在虚假陈述,导致专利被拒绝。 另一方面,如果说该机器是发明人,则专利局将拒绝该申请,因为发明人不是人。 像小林丸一样 ,重写规则是唯一的解决方案。

The Patent and Copyright Clause of the Constitution gives Congress the power to “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” This clause embodies the reason behind the patent and copyright system, which is to encourage innovation. People will be more inclined to invent things if they receive government-sanctioned monopolies for the commercial fruits of their inventions.[3]

《宪法》的专利和版权条款赋予国会权力“通过在有限的时间内为作者和发明家确保各自的著作和发现的专有权,来促进科学和实用艺术的进步。” 该条款体现了专利和版权制度背后的原因,即鼓励创新。 如果人们因其发明的商业成果而接受政府认可的垄断,他们将更倾向于发明事物。[3]

The statute, however, limits inventorship to natural persons. Under 35 U.S.C. § 100(a), “inventor” refers to “the individual or, if a joint invention, the individuals collectively who invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention.” Thus, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) opined that only natural persons could claim inventorship.

但是,该法规将发明人限制为自然人。 根据35 USC§100(a),“发明人”是指“个人,或者,如果是共同发明,则是集体发明或发现了本发明主题的个人。” 因此,美国专利商标局(USPTO)认为,只有自然人才能要求发明权。

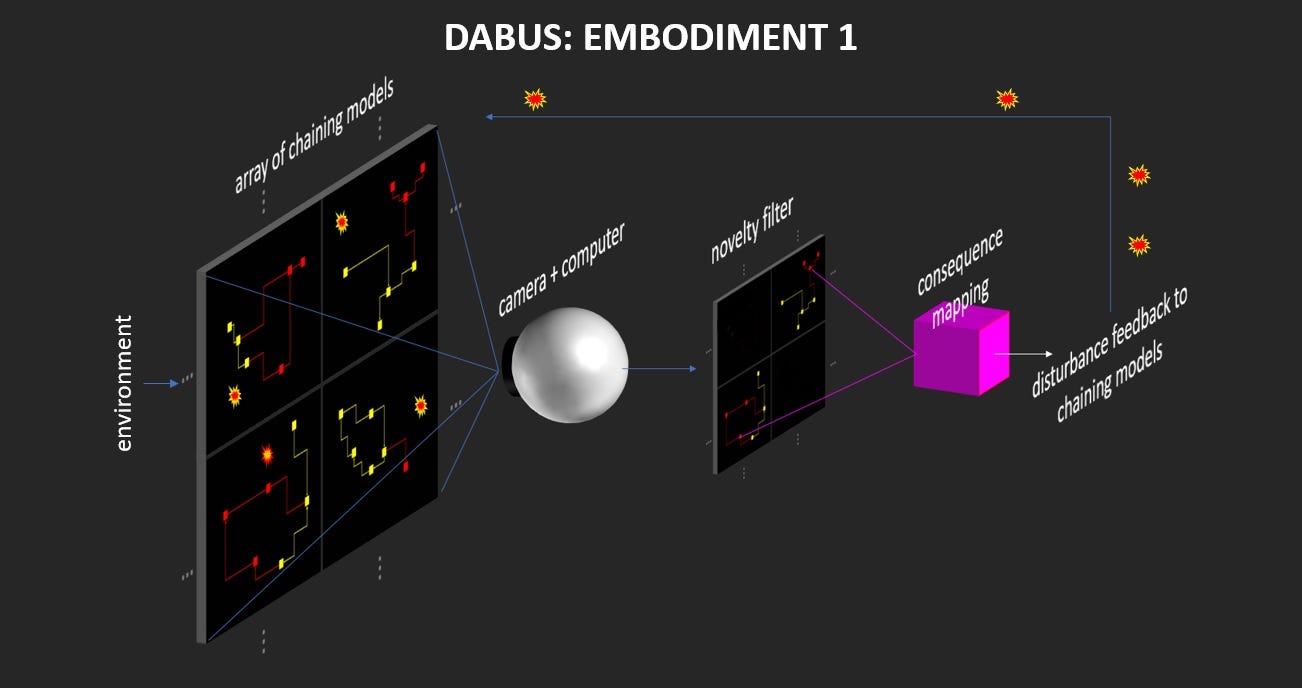

On April 27, 2020, the USPTO published a petition decision stating that only natural persons may be named as inventors in a patent application under current law. The agency’s decision stems from its rejection of a U.S. patent application that listed an autonomous entity, named DABUS, as the inventor. DABUS stands for “Device Autonomously Bootstrapping Uniform Sensibility” and is a “Creativity Machine” that uses neural networks to generate new inventions.[4] Back in August 2019, a group of patent lawyers called the Artificial Inventor Project (AIP) filed patents for two inventions — a warning light and a food container — on behalf of Stephen Thaler, CEO of a company called Imagination Engines. AIP listed DABUS as the inventor instead of a human author. According to AIP, the DABUS AI came up with innovations after being fed general data about many subjects. Thaler may have built DABUS, but he has no expertise in creating lights or food containers, and wouldn’t have been able to generate the ideas on his own. Hence, AIP argued DABUS itself is the inventor.[5]

2020年4月27日,美国专利商标局发布了一份请愿决定,指出根据现行法律,在专利申请中只有自然人可以被指定为发明人。 该机构的决定源于其拒绝了美国专利申请,该专利申请将名为DABUS的自治实体列为发明人。 DABUS代表“设备自主引导统一的灵敏度”,是一种使用神经网络产生新发明的“创造力机器”。[4] 早在2019年8月,一群名为人工发明家项目(AIP)的专利律师代表一家名为Imagination Engines的公司的首席执行官Stephen Thaler申请了两项发明的专利-警示灯和一个食品容器。 AIP将DABUS列为发明人,而非人工作者。 根据AIP的说法,DABUS AI在获得有关许多主题的一般数据后提出了创新。 Thaler可能已经建立了DABUS,但他在创建灯光或食物容器方面没有专门知识,也无法独自产生想法。 因此,AIP辩称DABUS本身就是发明者。[5]

One electro-optical embodiment of the DABUS paradigm. Image credits to Imagination Engines. DABUS范例的一种电光实施例。 图片归功于 Imagination Engines 。

One electro-optical embodiment of the DABUS paradigm. Image credits to Imagination Engines. DABUS范例的一种电光实施例。 图片归功于 Imagination Engines 。

The USPTO ruled that the patent statute precludes a broad interpretation to cover machines under the term “inventor.” By way of example, the office cited several sections of Title 35: “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter… may obtain a patent therefore, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title”[6]; “each individual who is an inventor… shall execute an oath or declaration in connection with the application”[7]; “[a]n oath or declaration under subsection (a) shall contain statements that… such individual believes himself or herself to be the original inventor”[8]; and “[a]ny person making a statement required under this section may withdraw, replace, or otherwise correct the statement at any time.”[9] The USPTO argues that the use of words such as “whoever”, “individual”, “himself”, “herself”, and “person”, implies that only a natural person can be an inventor.[10]

美国专利商标局(USPTO)裁定,专利法规不对“发明人”一词所涉及的机器进行广泛的解释。 举例来说,该局引用了标题35的几个部分:“ 凡发明或发现任何新的和有用的过程,机器,制造或物质组成的人……因此,可以根据该标题的条件和要求获得专利” [6]; “每个谁是发明者个人 ……应在与应用程序连接执行宣誓或声明” [7]; “[1]根据第Ñ宣誓或声明(一)应包含语句…这样的单独认为他或她自己是原始发明者” [8]; 以及“ [任何人根据本节要求发表声明时,都可以随时撤回,替换或以其他方式更正该声明。” [9]美国专利商标局辩称,使用“任何人”,“个人”, “他自己”,“她自己”和“人”意味着只有自然人才能成为发明者。[10]

The USPTO likewise cited some case law, such as Univ. of Utah v. Max-Planck-Gessellschaft zur Forderung der Wissenschaften e.V.,[11] explaining that a state could not be an inventor because it is incapable of conception,[12] and Beech Aircraft Corp. v. EDO Corp., ruling that “only natural persons can be ‘inventors.’”[13] While the USPTO admits that these decisions were rendered in the context of states and corporations, it believes that the discussion of conception as being a “formation in the mind of the inventor” and a “mental act” is equally applicable to exclude machines from the definition of “inventor.”

美国专利商标局也引用了一些判例法,例如大学。 犹他州诉Max-Planck-Gessellschaft zur Forderung der Wissenschaften eV案 [11]解释说,一个国家由于无能为力而不能成为发明人,[12]和Beech Aircraft Corp.诉EDO Corp.案 ,裁定: “只有自然人才可以是\’发明家\’。” [13]尽管美国专利商标局承认这些决定是在州和公司的背景下做出的,但它认为对概念的讨论是“发明家心目中的形成”。 “精神行为”同样适用于将机器从“发明家”的定义中排除。

Notably, it is not only in the U.S. that these patents were denied for the same reason. Applications were also filed with the U.K. Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) and the European Patent Office (EPO). While accepting that DABUS is responsible for the invention, the UKIPO ordered the application’s withdrawal because DABUS is not a person as envisioned by the law to be an inventor. The UKIPO however noted that AI inventions are likely to become more prevalent and that it is correct to debate these issues since the current patent system does not provide a means for handling such creations. On the other hand, the EPO ruled that the name of a machine does not meet the requirements of stating a family name, given names, and a full address of the inventor. The EPO further explained that legislation would be required to create a legal personality for AI systems or machines because “legislative history shows that the legislators of the EPC (European Patent Convention) agreed that the term ‘inventor’ refers to a natural person only.” The EPO also noted that this is the “internationally applicable standard” followed by the majority of the EPC contracting states, as well as China, Japan, Korea and the U.S.A.[14]

值得注意的是,不仅是在美国,出于同样的原因而拒绝了这些专利。 还向英国知识产权局(UKIPO)和欧洲专利局(EPO)提出了申请。 在接受DABUS负责发明的同时,UKIPO命令撤回该申请,因为DABUS不是法律规定的发明人。 不过,UKIPO指出,人工智能发明可能会变得更加普遍,并且辩论这些问题是正确的,因为当前的专利制度并未提供处理此类创造的手段。 另一方面,EPO裁定机器名称不符合陈述姓氏,给定名称和发明人完整地址的要求。 EPO进一步解释说,要建立AI系统或机器的法人资格将需要立法,因为“立法历史表明EPC(欧洲专利公约)的立法者同意“发明人”一词仅指自然人。” 欧洲专利局还指出,这是大多数EPC缔约国以及中国,日本,韩国和美国遵循的“国际适用标准” [14]

Naruto has no rights to the selfies he took, according to the US 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. 据美国第九巡回上诉法院称,火影忍者对其所拍摄的自拍照没有任何权利。

Naruto has no rights to the selfies he took, according to the US 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. 据美国第九巡回上诉法院称,火影忍者对其所拍摄的自拍照没有任何权利。

In the field of copyrights, the U.S. follows the same conservative approach. From as early as 1973, the U.S. Copyright Office has applied the “human authorship policy” that prohibits copyright protection of works that are not generated by a human author. This is the same policy brought into light by the famous “monkey selfies” case.[15] The People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) filed a claim on behalf of an Indonesian crested macaque, arguing that the monkey should own the copyright to the photographs.[16] The court dismissed the case and basically ruled that animals can’t sue for copyright infringement.

在版权领域,美国遵循相同的保守方法。 早在1973年,美国版权局就开始实施“人类著作权政策”,禁止非人类著作者对作品进行版权保护。 这与著名的“猴子自拍”案所揭示的政策是相同的。[15] 动物道德对待人民(PETA)代表印度尼西亚冠毛猕猴提出了一项要求,认为猴子应拥有照片的版权。[16] 法院驳回了此案,并基本上裁定动物不得起诉侵犯版权的行为。

But whether animals are capable of creating art is not exactly a pressing question for our time. The more critical issue is if computer-generated works can be copyrighted. In 1978, the National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyrighted Works (CONTU) reported to Congress that a computer could not be an author. “On the basis of its investigations and society’s experience with the computer, the Commission believes that there is no reasonable basis for considering that a computer in any way contributes authorship to a work produced through its use,” the report stated.[17] However, the CONTU compared the computer to a camera or a typewriter, both being instrumentalities that in themselves were utterly lacking in creative capabilities while requiring human direction to bring about an original result.[18]

但是,动物是否有能力创造艺术并不是我们时代的紧迫问题。 更为关键的问题是计算机生成的作品是否可以享有版权。 1978年,国家版权作品新技术使用委员会(CONTU)向国会报告,计算机不能为作者。 报告指出:“根据调查和社会对计算机的使用经验,委员会认为没有合理的依据来考虑计算机以任何方式对通过使用计算机产生的作品具有著作权。” [17] 但是,CONTU将计算机与照相机或打字机进行了比较,两者都是工具,它们本身完全缺乏创造能力,而需要人工指导才能产生原始结果。[18]

However, today’s technology is very different. With the emergence of AI software, computers have created and will continue to create original works that could be protected if not for the human authorship policy. Ryan Abbott, a patent attorney, and professor of health sciences at the University of Surrey in the U.K., is among the lawyers working on the AIP. In his article, I Think, Therefore I Invent: Creative Computers and the Future of Patent Law,[19] he concludes that computers independently meet the requirements for inventorship, but the statutory language requiring inventors to be individuals and judicial characterizations of the invention as a “mental act” present barriers to computer inventorship.[20]

但是,今天的技术却大不相同。 随着AI软件的出现,计算机已经创造并将继续创造原创作品,这些原创作品即使不受到人类著作权政策的保护,也可以得到保护。 英国萨里大学的专利律师,健康科学教授瑞安·阿伯特(Ryan Abbott)也是从事AIP工作的律师之一。 他在他的文章《 我认为,因此发明了:创意计算机和专利法的未来》 [19]中得出结论,计算机独立地满足了发明人的要求,但是法定语言要求发明人必须是个人,并且将发明的司法特征描述为“心理行为”为计算机发明创造提供了障碍。[20]

If a machine can think, it would seem logical that it could compose or design. If AI does create something, such as a piece of music, and it is impossible to tell by hearing whether it was written by a computer or by a person, one might wonder if the notion of machine authorship ought to be accepted.[21] The U.S. has not made reforms to address this, but some parts of the world have initiated actions to keep the field of copyright adaptive with the advances in technology. As early as 1988, the U.K. Copyright, Designs and Patents Act recognized a “computer-generated” work as one without a “human author” and granted such work copyright protection. In 2017, the European Parliament advocated giving autonomous robots the legal status of “electronic persons” for copyright protection purposes. Also, the Delegation of the European Union to Japan met in Tokyo to discuss, among others, whether AI-generated works are copyrightable under Japanese and European law.[22]

如果一台机器可以思考,那么它可以组成或设计似乎是合乎逻辑的。 如果AI确实创造了某种东西,例如一段音乐,并且无法通过听到它是由计算机还是由个人编写来分辨,那么人们可能会怀疑是否应该接受机器著作权的概念。[21] 美国尚未进行改革以解决此问题,但世界上的某些地区已采取行动,以使版权领域随着技术的发展而不断变化。 早在1988年,英国《版权,设计和专利法》就将“计算机生成的”作品确认为没有“人类作者”的作品,并授予该作品版权保护。 2017年,欧洲议会主张出于版权保护目的,赋予自动驾驶机器人“电子人”法律地位。 此外,欧洲联盟日本代表团在东京开会,讨论AI生成的作品是否应根据日本和欧洲法律享有版权。[22]

The U.S. perspective in inventorship and authorship remains rooted in the traditional belief that only humans are capable of intellectual creation. However, this conclusion was reached only by analyzing creation issues concerning animals, corporations, and the state. Intellectual property considerations in works of machine creators vis-à-vis human creators are yet to be tackled by U.S. courts.

美国对发明家和作者身份的看法仍然植根于传统观念,即只有人类才能创造知识。 但是,仅通过分析有关动物,公司和国家的创造问题才能得出此结论。 美国法院尚未解决机器创造者相对于人类创造者作品中的知识产权问题。

That is not to say that there has been no movement for the recognition of AI inventors in the U.S. The USPTO acknowledged the emergence of creative technologies and their capability to produce otherwise patentable inventions.It hosted an event entitled “Artificial Intelligence: Intellectual Property Policy Considerations (January 2019).” Due to the unique issues with advanced technologies, the USPTO is considering whether it should make any changes to how it handles examination of these applications. For its analysis, the USPTO issued a request for public comments on the protection and study of these inventions. It even expanded the scope of its inquiry to cover copyright, trademark, and other intellectual property rights impacted by AI.[23]

这并不是说在美国没有认可AI发明者的动议。美国专利商标局承认创意技术的出现及其产生可以申请专利的发明的能力。它主办了一次活动,主题为“人工智能:知识产权政策考量” (2019年1月)。” 由于先进技术的独特问题,USPTO正在考虑是否应对其处理这些申请的方式进行任何更改。 为了进行分析,USPTO发出了对这些发明的保护和研究进行公众评论的请求。 它甚至将调查范围扩大到涵盖受AI影响的版权,商标和其他知识产权。[23]

However, absent any new legislation or case law recognizing AI inventors, the USPTO is unlikely to retract its opinion in the DABUS petition. Even with the policy considerations, this is actually a safe approach for the USPTO.[24] It would prefer to follow the plain language of the law and leave it to Congress or the courts to direct the office to do otherwise.

但是,由于没有任何新的法律或判例法认可AI发明者,因此USPTO不太可能在DABUS申请中撤回其意见。 即使有政策考虑,这实际上也是美国专利商标局的安全方法。[24] 它宁愿遵循法律的通俗易懂的语言,然后将其交由国会或法院指示其执行其他职责。

With the proliferation of AI capable of conception, how must the legal landscape adapt?

随着具有概念能力的AI的泛滥,法律格局必须如何适应?

Until the patent system is reformed, AI developers will tend not to disclose a computer’s participation in the inventive process to successfully obtain a patent. But this poses serious risks. For one, if the patent office is aware that the human is not responsible for the invention, the application should be denied.[25] Another problem here is exposing the applicant to liability. The listed inventor must sign an oath or declaration that such individual believes himself or herself to be the original inventor.[26] A false oath or declaration carries a severe punishment of a fine or imprisonment.[27]

在专利制度改革之前,AI开发人员将倾向于不公开计算机在发明过程中的参与以成功获得专利。 但这带来了严重的风险。 首先,如果专利局意识到人们不应对发明负责,则应拒绝该申请。[25] 这里的另一个问题是使申请人承担责任。 所列发明人必须宣誓或声明该人认为自己是原始发明人。[26] 宣誓不实或宣誓无效,将处以罚款或监禁。[27]

If a person who discovers the subject matter of the invention can be an inventor, why not list him or her instead rather than the machine? Abbott thinks that this would entail questions. AI may be functioning more or less independently, and it is only sometimes the case that substantial insight is needed to identify and understand a computational invention. In cases where a person just thinks of a problem to be solved, but the computer solves it with no contribution from the human, giving the person an incentive would be unfair.[28] There is also a logistical problem since the first person to notice and appreciate the solution would be deemed the inventor, regardless if he or she owns the AI or had any right to see the created technology at the outset.[29]

如果发现本发明主题的人可以是发明人,为什么不列出他或她而不是列出机器? 雅培认为这将引起疑问。 AI可能或多或少地独立运作,仅在某些情况下才需要大量的见识来识别和理解计算发明。 如果某人只是想到要解决的问题,而计算机却在没有人的帮助的情况下解决了该问题,则给该人以激励是不公平的。[28] 还有一个后勤问题,因为第一个注意到并欣赏该解决方案的人将被视为发明者,无论他或她拥有AI还是一开始就有权查看所创造的技术。[29]

According to Abbott, treating computational inventions as patentable and recognizing creative computers as inventors would be consistent with the Constitutional rationale for patent protection.[30] We already know that the foundation of patent law is the incentive theory. If the present law continues not to recognize machine inventors, innovation would be hindered without any form of legal benefit available to would-be developers of such machines. But if creative machines are accepted, although AI would not be motivated to invent by the prospect of a patent, engineers would be encouraged to develop more of these machines.[31]

雅培认为,将计算发明视为可授予专利,并将创意计算机视为发明者将与专利保护的宪法依据相符。[30] 我们已经知道专利法的基础是激励理论。 如果现行法律继续不承认机器发明者,那么创新将受到阻碍,而这种机器的潜在开发者将无法获得任何形式的法律利益。 但是,如果创意机器被接受,尽管专利的前景不会激发人工智能的发明,但将鼓励工程师开发更多此类机器。[31]

The financial benefit is particularly important since developing AI demands much resources.[32]Moreover, patents not only confer a right to use the invention but also a right to stop third parties from using or exploiting said invention. Of course, AI systems are already developing at a rapid pace and are generating many new technical solutions, patentable or otherwise. But if the patent system is re-wired to adapt to this new era, the appropriate party would have some form of control over the exploitation and dissemination of inventive ideas generated by AI systems.[33]

财务利益特别重要,因为开发AI需要大量资源。[32]此外,专利不仅授予使用发明的权利,而且还授予阻止第三方使用或利用所述发明的权利。 当然,人工智能系统已经在快速发展,并且正在产生许多可申请专利或其他的新技术解决方案。 但是,如果重新安排专利系统以适应这个新时代,那么适当的一方将对人工智能系统产生的发明思想的开发和传播具有某种形式的控制权。[33]

The “appropriate party”, i.e. owner of the patent, is not the computer. A patent remains to be property that only persons can own. Man may be too proud at present to recognize personality in machines. We will be keeping all our rights to ourselves as long as we can. Thus, the patent owner should still be an entity capable of owning property, whether it be a person, a corporation, or a state.

“适当的一方”,即专利的所有者,不是计算机。 专利仍然是只有人才能拥有的财产。 目前,人可能太骄傲以至于无法识别机器中的个性。 我们将竭尽所能保留自己的所有权利。 因此,专利所有人仍应是能够拥有财产的实体,无论是个人,公司还是国家。

Abbott suggests that, subject to contract, a computer’s owner should be the default assignee of any invention because this is most consistent with the rules governing property ownership and would most incentivize innovation.[34] He likens it to an employer-employee relationship, where the owner is the former and the machine is the latter. To illustrate, if Thaler is the owner and DABUS is the inventor, Thalus owns the patent to any of DABUS’ creations.[35] Like any of his properties, Thaler is of course free to sell, lease, license, or even donate, DABUS or any of his patents. His lawyers can be as creative as possible to craft terms to protect his interest. What is important is that at the creation of DABUS, Thalus is properly incentivized for producing an AI-inventor.

雅培建议,在遵守合同的前提下,计算机的所有者应是任何发明的默认受让人,因为这与管理财产所有权的规则最一致,并且可以最大程度地激励创新。[34] 他将其比喻为劳资关系,所有者是前者,机器是后者。 为了说明这一点,如果Thaler是所有者,而DABUS是发明人,那么Thalus拥有DABUS的任何创作的专利。[35] 像他的任何财产一样,Thaler当然可以自由出售,租赁,许可甚至捐赠DABUS或他的任何专利。 他的律师可以尽可能地发挥创造力来保护他的利益。 重要的是,在创建DABUS时,Thalus受到了激励来产生AI发明家。

With the evolution of AI and emergence of machine-created technical solutions, there is a need to address intellectual property issues that many innovators are facing. They have this dilemma among them on who should be listed as the inventor of products created by their AI. They are not comfortable in claiming all credit for themselves but at the same time, they fear exposing the invention to the public domain without the protection of a patent. With the haunting uncertainties, regulators must act to define rights arising from AI-created inventions. There will come a day when society will be looking to machines to come up quickly and efficiently with solutions. The incentive theory of patent law must remain as an existing policy to promote the creation of these kinds of AI. With so many challenging problems today, we need now more than ever to change the rules to encourage innovation.

随着AI的发展和机器创建的技术解决方案的出现,有必要解决许多创新者面临的知识产权问题。 他们之间存在两难选择,即谁应该被列为由其AI创造的产品的发明者。 他们不愿意为自己争取全部信誉,但是与此同时,他们担心在没有专利保护的情况下将发明公开给公众。 由于存在巨大的不确定性,监管机构必须采取行动来定义由AI创造的发明产生的权利。 会有一天,社会将寻求机器快速有效地提出解决方案。 专利法的激励理论必须作为促进此类AI创造的现有政策而保留。 当今有许多具有挑战性的问题,我们比以往任何时候都更需要更改规则以鼓励创新。

[1] See Robert Jehan, Should an AI system be credited as an inventor, http://artificialinventor.com/should-an-ai-system-be-credited-as-an-inventor-robert-jehan/.

[1] 参见 Robert Jehan,“ AI系统是否应被认为是发明者” , http://artificialinventor.com/should-an-ai-system-be-credited-as-an-inventor-robert-jehan/ 。

[2] Id.

[2] I D。

[3] See Ryan Abbott, I Think, Therefore I Invent: Creative Computers and the Future of Patent Law, 57 B.C.L. Rev. 1079 (2016), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol57/iss4/2, citing Mark A. Lemley and John Stuart Mill.

[3] 见 Ryan Abbott,《 我想,因此我发明:创意计算机与专利法的未来》 ,第57 BCL Rev. 1079(2016), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol57/iss4/2 ,引用Mark A. Lemley和John Stuart Mill。

[4] See Bereskin & Parr LLP — Isi Caulder and Ray Kovarik, USPTO: AI Cannot Be Named as Inventor on Patent, April 28, 2020, https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=73ac519f-7fbb-4206-9aba-c16e1bf731df.

[4] 参见 Bereskin&Parr LLP-Isi Caulder和Ray Kovarik, 美国专商局:AI不能被指定为专利发明人 ,2020年4月28日, https : //www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g = 73ac519f -7fbb-4206-9aba-c16e1bf731df 。

[5] See Angela Chen, Can an AI be an inventor? Not yet., January 8, 2020, https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/01/08/102298/ai-inventor-patent-dabus-intellectual-property-uk-european-patent-office-law/.

[5] 参见 Angela Chen, 人工智能可以成为发明家吗? 还没。 ,2020年1月8日, https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/01/08/102298/ai-inventor-patent-dabus-intellectual-property-uk-european-patent-office-law/ 。

[6] 35 U.S.C. §101.

[6] 35 USC§101。

[7] 35 U.S.C. §115(a).

[7] 35 USC§115(a)。

[8] 35 U.S.C. §115(b).

[8] 35 USC§115(b)。

[9] 35 U.S.C. §115(h)(1).

[9] 35 USC§115(h)(1)。

[10] Visit https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/16524350_22apr2020.pdf for the full text of the USPTO decision.

[10]访问https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/16524350_22apr2020.pdf ,以获取USPTO决定的全文。

[11] 734 F.3d 1315 (Fed. Cir. 2013).

[11] 734 F.3d 1315(联邦调查局,2013年)。

[12] The Federal Circuit explained in this case: “Conception is the touchstone of inventorship, the completion of the mental part of invention. It is the formation in the mind of the inventor, of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention, as it is hereafter to be applied in practice. Conception is complete only when the idea is so clearly defined in the inventor’s mind that only ordinary skill would be necessary to reduce the invention to practice, without extensive research or experimentation. [Conception] is a mental act…”

[12]在这种情况下,联邦巡回法院解释说:“构思是发明创造的试金石,是发明精神部分的完成。 发明人心目中对完整和可实施的发明有明确而永久的构想,这将在以后的实践中应用。 仅当发明人脑海中清楚地定义了一个想法,而无需进行大量研究或实验时,只有普通技能才能使发明付诸实践,构思才算完成。 [构思]是一种精神行为……”

[13] 990 F.2d 1237, 1248 (Fed. Cir. 1993).

[13] 990 F.2d 1237,1248(联邦法院,1993)。

[14] See Rebecca Tapscott, USPTO Shoots Down DABUS’ Bid For Inventorship, May 4, 2020, https://www.ipwatchdog.com/2020/05/04/uspto-shoots-dabus-bid-inventorship/id=121284/.

[14] 参见丽贝卡· 塔普斯科特(Rebecca Tapscott), 美国专商局(USPTO)拒绝了DABUS的发明报价 ,2020年5月4日, https: //www.ipwatchdog.com/2020/05/04/uspto-shoots-dabus-bid-inventorship/id=121284 / 。

[15] See Naruto v. Slater, №16–15469 (9th Cir. 2018).

[15] 见《火影忍者诉斯莱特》,№16–15469(9th Cir。2018)。

[16] See Ryan Abbott, The Artificial Inventor Project, December 2019, https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2019/06/article_0002.html.

[16] 见 Ryan Abbott, 《人工发明家计划》 ,2019年12月, https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2019/06/article_0002.html 。

[17] See CONTU Final Report (1979) at 44.

[17] 见 CONTU最终报告(1979),第44页。

[18] Id.

[18] ID 。

[19] See Abbott, supra note 3.

[19] 见雅培, 前注3。

[20] Id. at 1083.

[20] ID。 在1083。

[21] See Pamela Samuelson, Allocating Ownership Rights in Computer-Generated Works, 47 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 1185 1985–1986.

[21] 见帕梅拉·萨缪尔森, 《在计算机生成的作品中分配所有权》,美国皮特出版社47页。 L. Rev. 1185 1985–1986。

[22] See Edward Klaris, Copyright laws and artificial intelligence, December 2017, https://www.americanbar.org/news/abanews/publications/youraba/2017/december-2017/copyright-laws-and-artificial-intelligence/.

[22] 见爱德华·克拉里斯,《 版权法和人工智能》 ,2017年12月, https: //www.americanbar.org/news/abanews/publications/youraba/2017/december-2017/copyright-laws-and-artificial-intelligence/ 。

[23] See Artificial Intelligence (AI) Patents — Will the Patent Office Change the Rules?, January 7, 2020, https://www.natlawreview.com/article/artificial-intelligence-ai-patents-will-patent-office-change-rules.

[23] 参见人工智能(AI)专利-专利局会更改规则吗? ,2020年1月7日, https://www.natlawreview.com/article/artificial-intelligence-ai-patents-will-patent-office-change-rules 。

[24] The USPTO stated: “Lastly, petitioner has outlined numerous policy considerations to support the position that a patent application can name a machine as an inventor. For example, petitioner contends that allowing a machine to be listed as an inventor would incentivize innovation using AI systems, reduce the improper naming of persons as inventors who do not qualify as inventors, and support the public notice function by informing the public of the actual inventors of an invention. These policy considerations notwithstanding, they do not overcome the plain language of the patent laws as passed by the Congress and as interpreted by the courts.”

[24]美国专利商标局说:“最后,请愿人概述了许多政策考虑因素,以支持专利申请可以将机器命名为发明人的立场。 例如,请愿人认为,允许将某台机器列为发明人会激励使用AI系统的创新,减少不符合发明人资格的人的不当命名,并通过向公众告知实际情况来支持公众通知功能。发明的发明人。 尽管有这些政策上的考虑,但它们并没有克服国会通过和法院解释的专利法的通俗易懂的语言。”

[25] See USPTO decision in the DABUS petition, supra note 10.

[25] 见美国专利商标局在DABUS请愿书中的决定, 上文注10。

[26] 35 U.S.C. § 115(a) and (b).

[26] 35 USC§115(a)和(b)。

[27] See Robert Jehan, supra note 1.

[27] 见罗伯特·杰罕(Robert Jehan), 前注1。

[28] See Abbott, supra note 3.

[28] 见雅培, 前注3。

[29] Id.

[29] ID 。

[30] See Abbott, supra note 3.

[30] 见雅培, 前注3。

[31] Id.

[31] ID。

[32] Id.

[32] ID。

[33] See Robert Jehan, supra note 1.

[33] 见罗伯特·杰罕, 前注1。

[34] See Abbott, supra note 3.

[34] 见雅培, 前注3。

[35] See Angela Chen, supra note 5.

[35] 见 上文注5的Angela Chen。

翻译自: https://medium.com/@aa2689/robot-inventors-69fc095c8482

ai 实用新型专利

爱站程序员基地

爱站程序员基地

![[翻译] Backpressure explained — the resisted flow of data through software-爱站程序员基地](https://aiznh.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/29-220x150.jpeg)